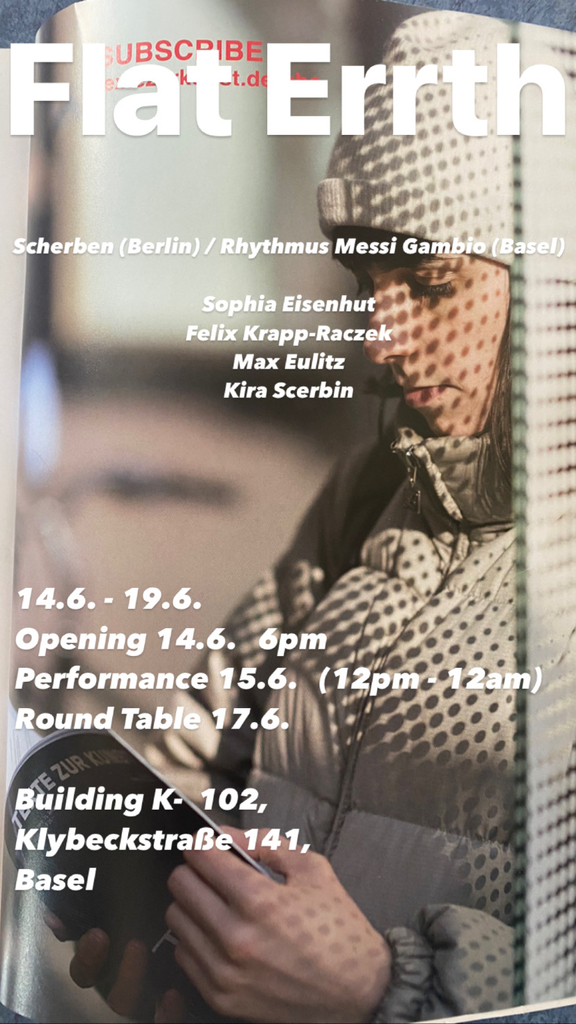

Flat Errth

Sophia Eisenhut, Felix Krapp-Raczek, Max Eulitz, Kira Scerbin

at Rhythmus Messi Cambio (Basel), initiated by Scherben

“The Dadaist is a realist (Wirklichkeitsmensch) who loves wine, women, and advertising,” wrote Richard Huelsenbeck, known as the “Reklame-Dada,” in 1920. By subsuming advertisement to the category of realism, Huelsenbeck sought to counter other poets and artists, mostly expressionists, who held a sentimental resistance to modern life, that, in the 1920s was one of increasing semioticization: ads, signs, postered walls, advertising pillars, newspaper stands, “Heuschreckenschwärme von Schrift” (Walter Benjamin). The Dadaists understood the expressionists’ hatred of press and advertising as typical of “people who prefer their armchair to the noise of the street.” Hans Arp echoed this view in a retrospective account of his chance-based writings for which he incorporated text selected at random from newspapers: “Wir meinten durch die Dinge hindurch in das Wesen des Lebens zu sehen, und darum ergriff uns ein Satz aus einer Tageszeitung mindestens ebenso sehr wie der eines Dichterfürsten.”

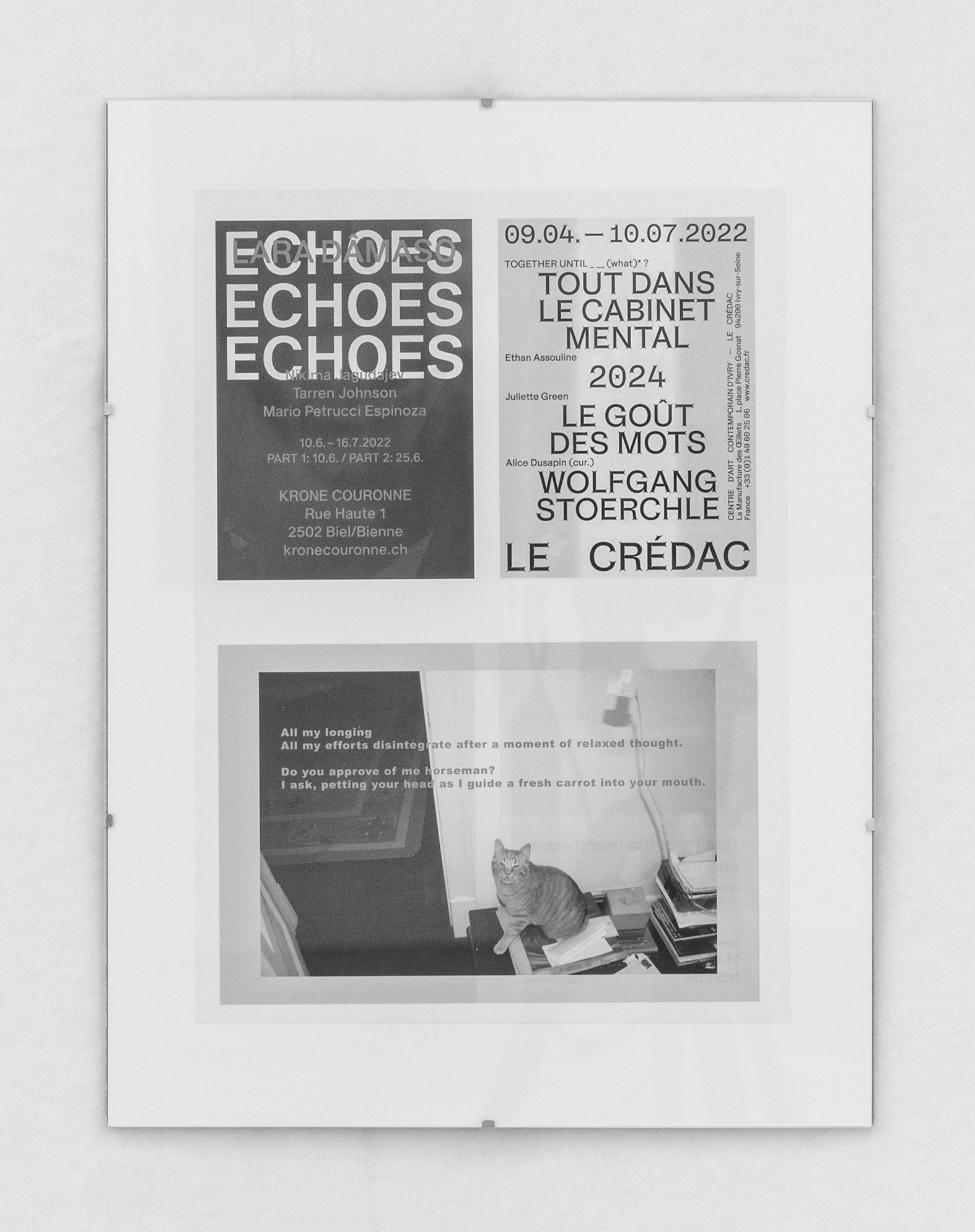

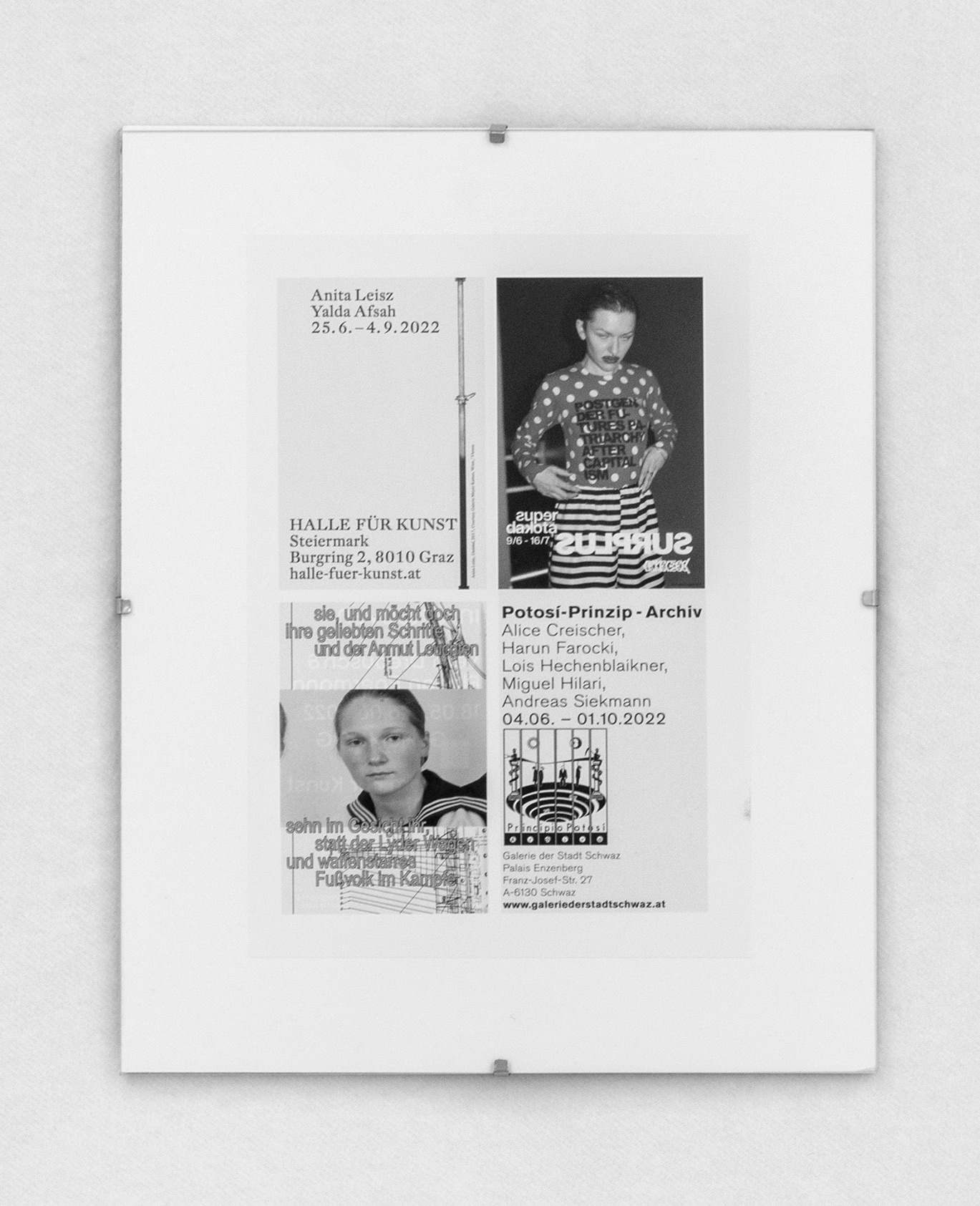

Updating Dadaism’s remix of the language of commodity promotion and that of poetic imagery, artists Sophia Eisenhut, Max Eulitz, Felix Krapp-Raczek, and Kira Scerbin —on invitation of the independent Berlin-based art space Scherben—placed different advertisement artworks, collages of found and self-created images and text fragments, in the summer issues of Artforum, Frieze, Monopol, Mousse, Passe Avant, Provence, Spike, and Texte zur Kunst, using Dada techniques for a critical evaluation of the current state of the art magazine world, a rather flat earth.

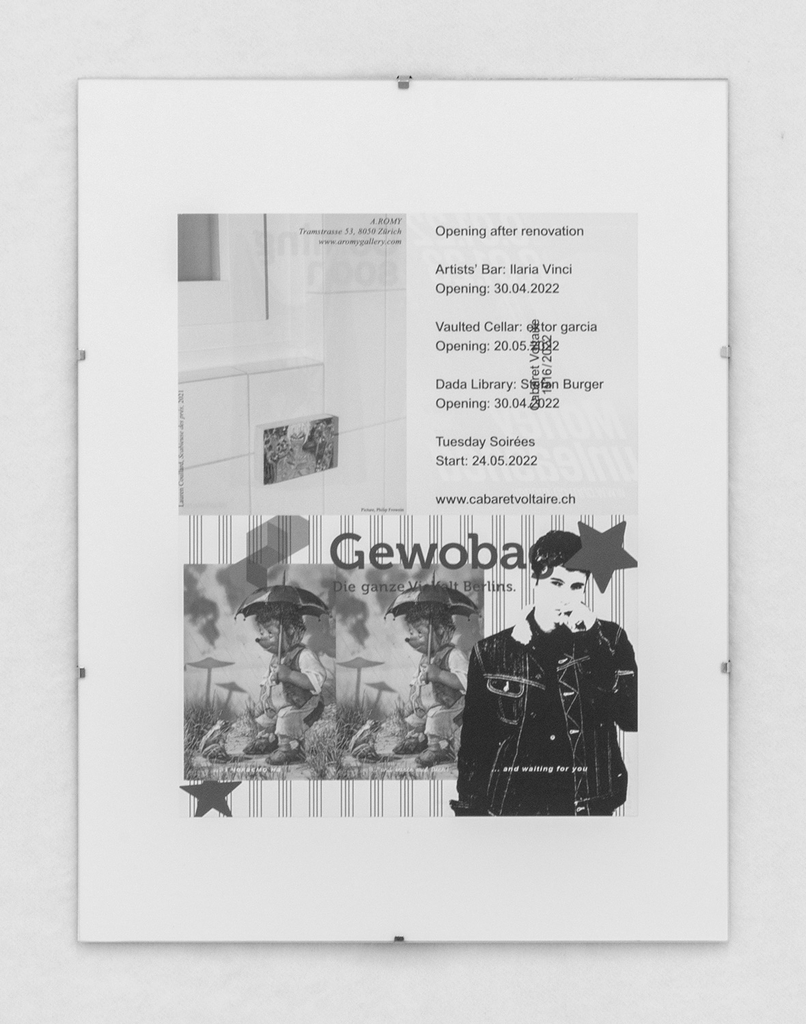

Somewhere between critique, nonsense and self-referentiality, the ads appropriate the Dada approach to advertising, often dismissed as a provocative self-promotional gambit or reduced to a simple satire of bourgeois consumer culture, to attack the intersection of art and commerce, both in the flat space of the art magazine and the blown up materiality of the financial art market. During Art Basel, the ripped out magazine pages were presented as framed editions in the independent art space Rhythmus Messy Cambio, turning relatively valueless flat prints into three-dimensional, buyable wall objects. As a self-declared “meta exhibition,” the exhibition “Flat Errth” not only aims at a critical investigation of the medium of the ad, but also of the sites of its circulation, magazine pages and art fairs.

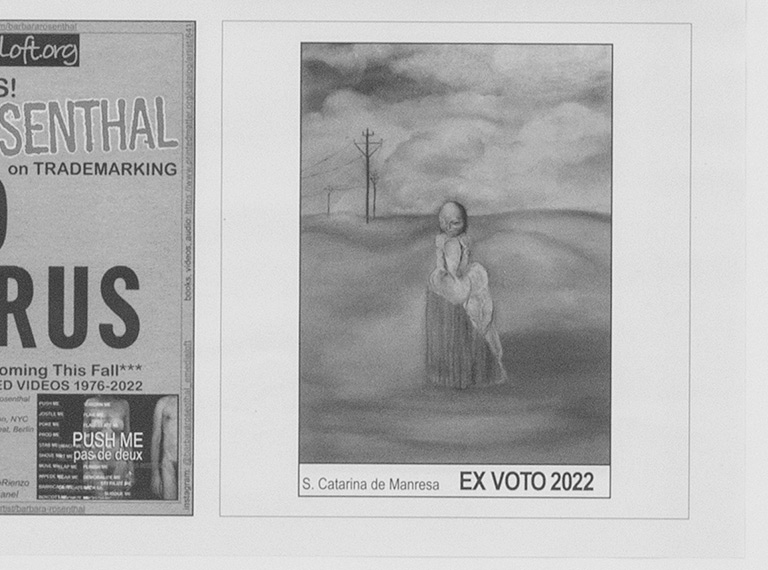

For the Provence issue on real estate, Max Eulitz and Felix Krapp-Razcek placed the logo of the Berlin real estate company Gewobag (“Die ganze Vielfalt Berlins”) next to a cool guy in a denim jacket, lasciviously smoking and saying “waiting for you.” The slogan, ornamented with emo stars, reads less like a sexy cheesy pick-up line than a real threat posed by the cruelty of the Berlin housing market. Advertising as storytelling, a fiction realizing itself through the promises of commodities and the cruel optimism of the good life. In Artforum, the art magazine gets caught up in its own hyperstition. Here, Sophia Eisenhut and Kira Scerbin placed an ex-voto-drawing of an alien version of S. Caterina de Manresa, the (anti-)protagonist of Eisenhut’s book EXERCITIA S. Catarinae de Manresa. Anorexie und Gottesstaatlichkeit inside a depressed, apocalyptic landscape left with only some power poles, perhaps an allegory for the contemporary art scenery itself. The advertisement is figured as a votive image, the commodity (offered by advertising and criticism) a promise of salvation. As motif of the votive, votary, symbolic sacrifice and saint, Catarina seems to embody the ambiguous role of contemporary art criticism: friendship service or distant outside perspective, advertisement or damning review, criticism as its own art form or criticism in service of art’s salvation?

For an ad in Spike Magazine’s issue on art and crime, an illustration from Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom, or the School of Libertinage, written while he was imprisoned in the Bastille, serves as the backdrop for a mirrored version of the Nestlé logo birds (reminiscent of the Situationists’ détournement ads) that reads, “mimesis is murder / diegesis is innocent.” All adorned with human blood, perhaps from cutting and tearing apart art magazines. Given the exhibition title “Flat Errth,” an appropriation of a right-leaning, anti-science conspiracy theory insisting on the disc shape of the Earth, this take on violence, sadism and morality might be read as a commentary on Ana Teixeira Pinto and Kerstin Stakemeier’s controversial “Glossary of Social Sadism” published in Texte zur Kunst’s 2019 “Evil” issue. The text surveys the pathology of an art milieu that rejects the repoliticization of contemporary art or any form of social responsibility, flirting instead with the language and symbols of the alt-right. The art sadist’s “categorical rejection of any scrutiny over one’s own implications in the perpetual oscillation between subjectivization and subjection under the cloak of ‘artistic freedom’ or ‘freedom of speech,’” is, according to Teixeira Pinto and Stakemeier, symptomatic of a “wounded narcissism, unable to divest from the pleasurable investment in the (increasingly besieged) notion of its own universality. Nursing its injury, it sets out to injure.” Spike Magazine, perhaps feeling provoked and offended by the text, responded with an issue on “Immorality” (which, funnily enough, is misspelled as “immortality” on their website: “Immortality is a response to the widely held idea that art needs to be moral. The world’s fucked up, and the art world is guilty too, so in some ways that makes sense”)—and a round table on “Cancel Culture” including edgelords Mathieu Malouf and Nina Power. Despite or because of the polemics on both sides, this was one of the more interesting art critical debates of recent years, playing out between two of the most influential art magazines and serving real antagonist positions rather than the usual IAE and polite reviews symptomatic of a criticism in crisis.

Today, the art critic functions both as a “citizen of a thoroughly financialised present” (Stakemeier) and, as cultural critic and lesbian icon Jill Johnston described it when calling for the disintegration of criticism, as “an unpaid publicity agent.” In the press release of the panel discussion “The Disintegration of A Critic—An Analysis of Jill Johnston,” she writes: “My purpose […] was to offer my name as a sort of sacrifice if you like for the idea of a disintegration of criticism, which I view as an outmoded form of communication. Reportage may be necessary and interesting. I like it myself. Poetry and all forms of fiction, history, autobiog., etc., I accept as forms of speech and writing not coercive as to the salesmanship of immediate artistic events, i.e., reviews in the newspapers and the magazines.” In “Flat Errth,” it is the form of fictional advertising rather than sell-out art criticism that takes on the role of critique. While art criticsm is confronted with an unsolvable dilemma—“that critique must insist on the fiction of another world and standard of value while remaining embedded in capitalist relation”—as Isabelle Graw and Sabeth Buchmann write in a 2019 essay on art criticism and discrimination published in Texte zur Kunst, advertisement can easily circumvent the question of complicity, as its economic embeddedness and compulsion to sale are its very conditions of existence.

Graw and Buchmann argue not to cling to “romantic stock fantasies of subversion” but to focus on the counter values immanent to the system, a position also held by art theorist Marina Vishmidt who propagates a critique that moves beyond the comfort zone of reflexivity, a critique that makes cuts and takes it upon itself to find or make the gaps and voids through which the infrastructure of art comes into view and which, in the undiminished awareness of negativity, holds the possibility of the better.

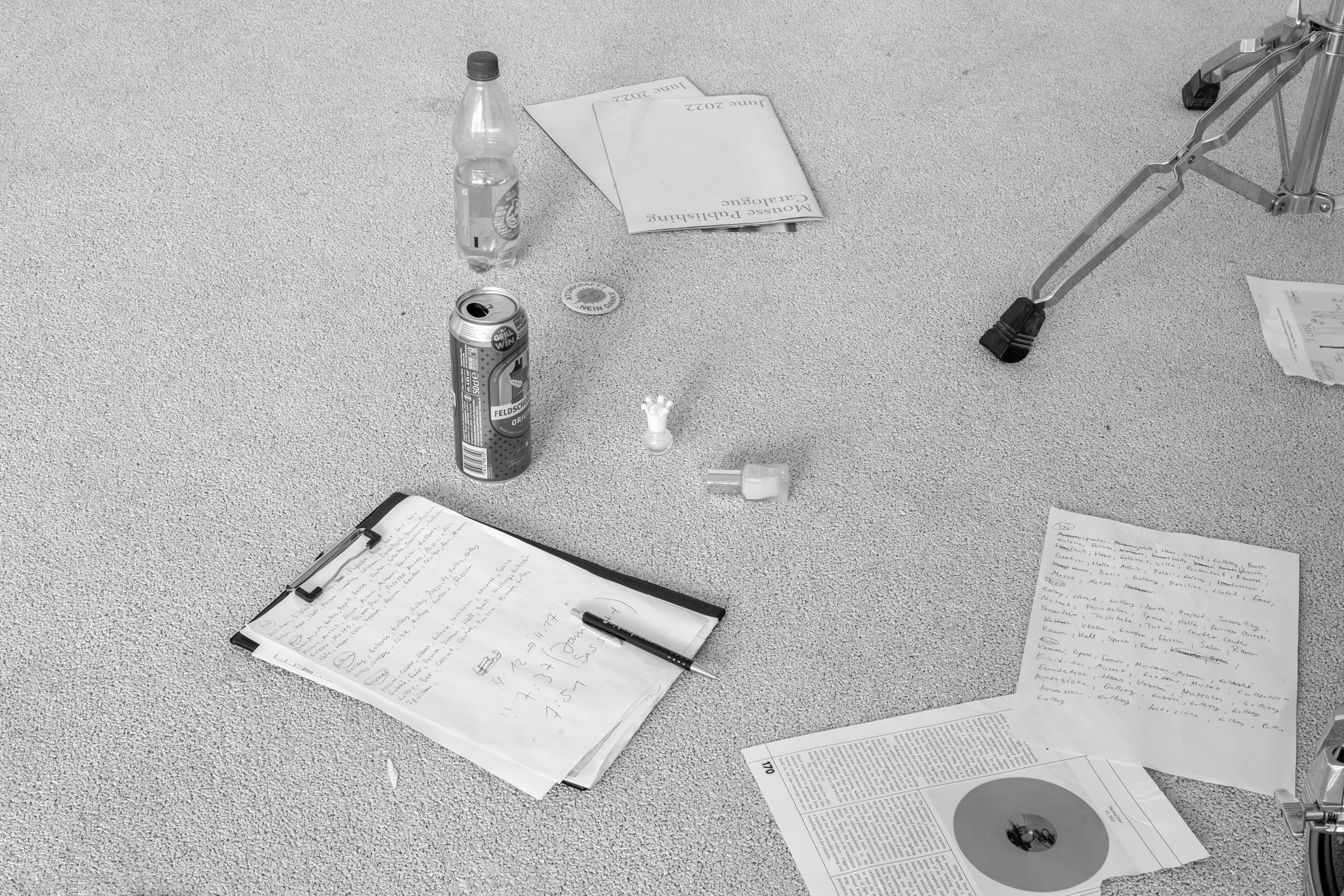

The presentation of the ads at Rhythmus Messy Cambio in the enigmatic building K-102, shared by a Jungle Yoga community and a local padel club, during Art Basel in the eponymous Swiss city, the annual proof of the possibility or even necessity of a smooth simultaneity of a “radical” critique of the capitalist value form of the artwork and a fetishization of the same, was accompanied by an enduring twenty-four-hour performance during which the artist quartet produced an album. It’s a mix of music, sound poems, spoken word (based on and sampled from texts in the art magazines in which Eisenhut & Co placed their ads), and often silence. The record is loosely based on scores consisting of attitudes and structures of feeling rather than strict musical instructions: verses without words, audience insults, nihilism, chance, low key, slow pace, improv, fun, humble, casual, modest punk, life in papers, friendship, unpretentious, drugs, comfortability. This remix of punk and coziness describes well what went on at Rhythmus Messy Cambio. While someone played the guitar gently, perhaps weeping, others cut and tore out magazine pages, bleeding, reading out single words from the art magazines, “propaganda” or “propagandada” (all in socks on a carpeted floor). A rock’n’roll and chill performance, a concert, recording, rehearsal, a hang-out spot, an after party, a lasting insignificance.

Creeping into the pages of the world’s leading art publications and thus inscribing themselves into the canon of art criticism, “Flat Errth” dodges the pretense of performing critique from a place outside economic and institutional structures, claiming and insisting instead on a place inside, while simultaneously looking at it from above (meta), being against it (anti) and not caring at all (exhaustion). “Flat Errth” performs a critique that is critical of critical distancing, understanding it, like Andrea Fraser, as “a form of negation in the psychoanalytic sense: a defensive maneuver that serves to disown the emotional investment in the object of critique and especially desire for that object, including identificatory or narcissistic desire.” But rather than dramatically acting out these affective investments in the object of critique (the art space, the magazine, the fair), here, in a punk anti-attitude, a fake-meta position and in the style of hot but exhausted millennials, they are reduced to a bare minimum, a calm, relaxed attitude in the face of one’s own entrapment, throwing themselves, quite comfortably, in the container that contains them.

by Sophia Roxane Rohwetter