June 10 – July 10 2022

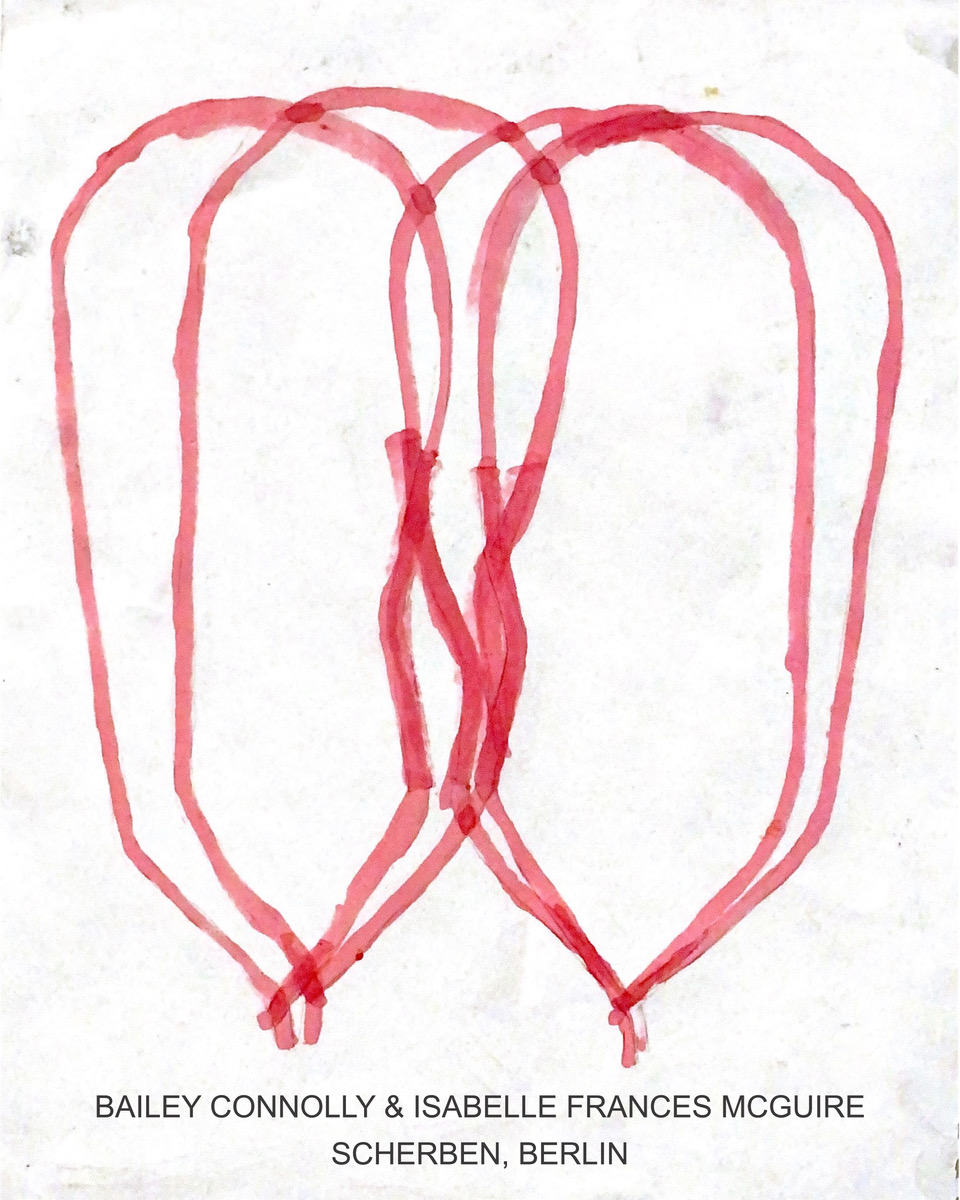

Bailey Connolly & Isabelle Frances McGuire is the second exhibition by the two artists in as many years, following their debut Dresses Without Women, at Mickey, Chicago in 2021.

For this exhibition McGuire’s breathing, blinking, grinning historical cosplay sex automotons have been reduced to a small metal enclosure connected to an amplifier. Inside the enclosure, two filtered oscillators produce sine waves, utilized for their relation to the human voice, that reverberate at a constant throughout the space. Two heart shaped sockets frame LEDs that blink in patterns which correspond to data-sets visualizing the heart beats of McGuire and Connolly, evidenced by the letters “b” and “i” in the title. Here, in lieu of the automaton’s life-size cosmetic likeness, the body’s kinetic physical properties have been severed to reveal their essential components. The speaking voice and beating heart become surrogate equivalents of the oscillator, knob, and light emitting diode. Accompanying the synthesizer are two images that function as a kind of memento mori for the transformations described above. The framed still life photographs with black mat document the lifeless 3D printed skulls of the absent life-size automatons before the application of silicone, hair, pigment, and animation- a moment of the life or death cycle only possible in the non-living-living entities of our present robotics age.

Two large painted foam sculptures titled ex (crush) and b (crush) occupy the floor of the gallery. Connolly’s forms are resonant of cattle crush apparatuses that are used to hold animals in place while being examined to minimize the risk of injury to both the animal and its operator. Cattle crush technology was famously appropriated for use by people with autism spectrum disorders who find relief in the physical sensation of being hugged without any direct human contact. Like the initials in McGuire’s heart beat visualizer, the titles of these works suggest multiple readings beyond reference to the individual forms themselves. It is not hard to imagine Connolly’s allusion to the self and others behind the variables “b” or “ex” and also, given the fate of the cattle being held on their way to extermination, their absence. The decision to retitle and repaint ex (crush) for this exhibition is also telling. Produced at a smaller scale relative to the size of the animal itself and not the referent machine, these works ask to be considered as both subject and object. Like Connolly’s sculptures of modernist housing reduced to the bare minimum parameters for ethical lab mice habitation, the shift in scale recalls the skeleton of the animal subject. The architecture of the apparatus has seemingly come to replace the object of the machine’s intended function.

KW